What is it that Australia owes to the Danish even nowadays? This is a story of a visionary and his life-long project, which was going to change everything, but it was going to cost him more than he could afford to pay. These are the excerpts of Jorn Utzon’s broken vision and his grand Opera.

Conceptually simple, but designer-wise elusive and complex project was going to become a national signature of young Australia. The time was just right and one manhad a vision of an artistic area that would be functionally and visually perfect. However, any perfection back then was destined to be under public scrutiny and limited by different political streams.

People nowadays talk about this project as a new dimension in the world of architecture, a tipping point of the famous achievements and the biggest architectural and designer endeavour of the 20thcentury. However, over the course of many years it was going to be judged as a failure, complete fiasco, and unnecessary expense. Whoever needs an opera house in Sydney?

A promising beginning

Sydney, Australia, 1950’s

Wide streets, green parks that smell like freshly cut grass. Wild Pacific waves rear up and crash down onto the rocks in the port Darling where the boats from all around the world dock; they rear up again and become a surfer heaven on Bondi beach. Australians felt free – in this young country from the 1950s there was this feeling that everything was possible, they were open to the whole world. They liked leisure activities – football was a religion, beer was the drink they were selling the most, and horse race betting was Sunday tradition in which 400 thousand pounds that Australians used back then were invested weekly.

People were awake, active, live. To be considered as a true Australian was to be politically and socially active member of the society who was proud of their difference and freedom. The country was being built up, the nation was coming of age. In the distance, one could see an exciting future of the country ‘from the other side of the world’.

Back then, Australia was considered to have a ‘sponge culture’. It meant that it was absorbing everything from the other side of the Pacific. The construction of such extravagant building like Opera was, which was built as a prestigious place for top-notch artistic performances, meant that Australia was becoming an important member of the world art milieu. The Sidney Opera House represented a bridge towards widespread world of culture, something that no everyone valued equally.

Copenhagen, Denmark, 1957

Ten-year-old Lin runs toward the phone. On the other side, an unknown male voice says that Mr Jorn Utzon is the winner of the New South Wales competition for Opera construction in Sidney. The voice serious and words sound important, but no one from the Utzons cannot foresee what those words are to bring.

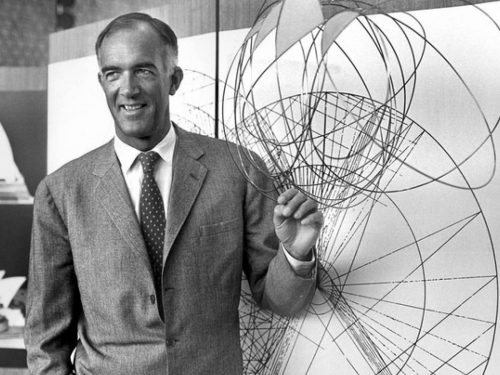

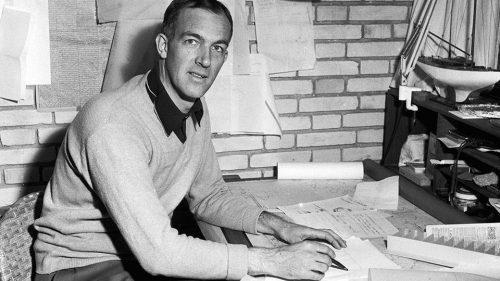

Jorn Utzon was born in April 1918 in Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark. As a son of a naval architect, he gradually developed a refined taste for art, subtle lines, and shape. Young Jorn learnt from his father how to observe nature and use it as a source of inspiration to create harmonic shapes. By the age of 38, he had already obtained a degree from Royal Danish Academy of Applied Arts, he had an architecture firm which won several prizes on competitions for local projects, and a reputation of uncompromising independent perfectionist.

Having been in love with nature, light, and reflection, he tried to keep every slope intact; everything he built was in perfect harmony with its location.

The location itself was the reason that made Jorn apply for the open competition for construction of the first opera in Australia. The building site meant for its construction was perfect in Jorn’s opinion; several hundred metres away from the downtown yet isolated enough to emphasise the special features of the new project in the above mentioned Benelong port. What used to be a warehouse became the ground for a masterpiece.

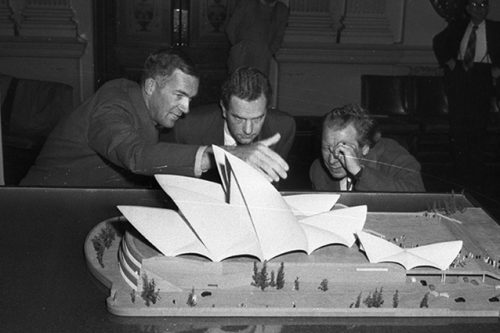

Taking into consideration the salient position, the new symbol of Sidney couldn’t have flaws. Utzon thought about each detail, which many might consider irrelevant. The Great Danish, as the media soon named him, set a task for himself to build a rare, incredible machinery for art performances, and he knew that it had to be perfect. The ideas were piling up, and eventually he had a final image of the project in his head. The deadline for submitting the conceptual layout plan to the New South Wales Committee was too soon for Utzon to pay attention to details, so he submitted his proposal which broke several competition rules – the conceptual layout plan looked more like a diagram, without detailed explanations and cost estimations. Simply, it was a sketch of a vision. Jorn was sure about the quality of his work, but he didn’t know if the Australian Committee of the architects would be able to imagine Sidney Opera House with the same passion as its maker, the way he had it imagined from the first day.

Philistine fears

As soon as Utzon arrived in Sidney, he started working on the project. It required time and patience, which was not something that the people of Australia approved of. Two years of the active work on the construction plan had barely gone by, when everyone lost their patience and wanted to wait no more. Jorn and his team were obliged to start in 1959, four years before it was planned. The early start was a political necessity, but architectural disaster. All those mistakes that existed on paper would now be imprinted into concrete and steel. However, it was clear that the art would have to give in to politics and bureaucracy.

Two amphitheatres emerge from the concrete platform – the big one for opera concerts and ballet, and the smaller one for plays. Two long staircases from the foyer to the top of the hall lead to the seats overlooking the main stage, which contains nine lifts that lead to the ground floor built for scenographic needs. There are also smaller theatre and chamber music hall. The ideas were clear, but the early start of works and the big number of changes made later, constantly set new challenges for Utzon and his engineers, all of which made only the basis of the project cost three times more than planned at first.

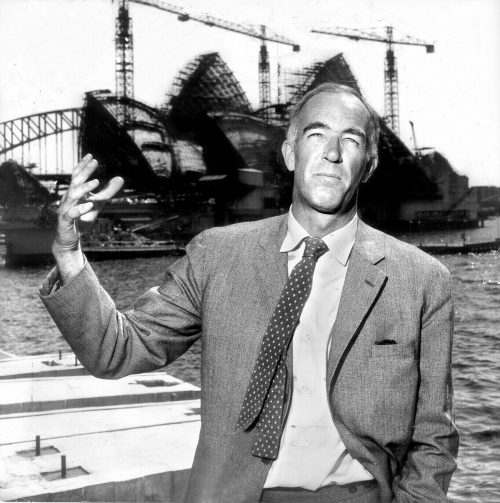

The time was passing by, and the perfect structural solution for the roof was still not found. In September 1961, the Danish genius got the idea. He understood that in order to find a solution for the complex design of the roof, he had to come back to the basic forms. He noticed that the parabolas he planned to use at first proved to be very complicated for construction, so he decided to start with a spherical shape instead, which he could use later to get the rest of the forms – this made the calculations simpler. These shapes of the individual ribs cut out from one shape were easy to mass-produce and accurately position on specific places, which is why, nowadays, we can talk about the white sails of Sydney. Years later, Jorn explained that he was inspired by something completely different – peeled orange, cut by a sharp knife. The final construction had 2194 parts weighing up to 15 tons.

How to estimate the value of something that has never been built before? What is the true price of a piece of art? How much would you pay for it?

At one point, the Sydney Opera House was 6,ooo metres squared scandal and the focus of a national debate on how much art is worth. Wide unfurled white sails were there, but the dreams about cruising off with those sails started falling apart slowly.

The focus of the national debate became the budget assigned for the Opera, or better said the excess thereof. Jorn felt that unfriendly attitudes were being formed not only on the side of people of Australia, but on the side of his colleagues too, engineers who were tired of his perfectionism and his ‘vision which only the rare ones understood’.

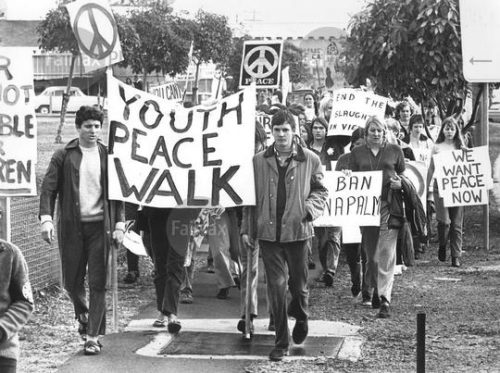

The rumours about millions of pounds Australians used back then, which ‘were wasted because they could have been invested in construction of new schools and hospitals’ became a part of an everyday conversation and one of the topics to fill out awkward silence with in trivial encounters. There weren’t as many rumours about millions of pounds that New South Wales used to spend on the previously mentioned horse bets tradition. This was a clear proof that the people did not have as many reprimands on how much money was spent, rather on where that money was going. Again, whoever needed an opera house?

Until 1960s, the costs rose 4 times. These numbers became the focal point of discussions and they successfully painted an image of the government, which completely lost the control over the project. The media enjoyed the melodrama between the artist on the one side, who by default is irresponsible, and the politicians on the other, who ‘wanted the best for their people’.

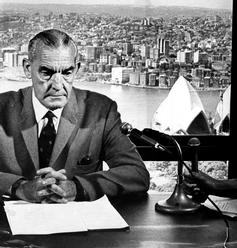

One of them, the newly elected Minister of Public Works played the key role. David Hughes represented a piercing voice of the political opposition and the constant critic of Utzon’s project.With his persuasive political speeches and pragmatic approach, Hues encouraged Australians to scorn his work, the project, and at the end, the architect himself. The public voice became discouraging silence of a presumed failure. Every step that the new minister made took a toll on Jorn’s vision. His vision required patience, understanding, and time. Hughes had none of these.

Australian benefactors’ intolerance toward Jorn hindered the project severely. The project slowed down and Hues eventually stopped paying Jorn and his team. Jorn was offended, but even more so convinced that no one else could finish the project so he left it. He left the Opera, Sydney, Australia.

While he was leaving the city with his family, he was looking at his grand unfinished project through the window. Jorn was never that close to it again. Opera was finally finished in 1973, and Jorn did not attend the opening. He never came back to Sydney and he never accepted any calls that followed afterwards.

Following years he spent working on the projects worldwide, carefully measuring every word uttered to the public. He accepted the fact that someone else was finishing something that his mind gave life to. He did not go back to the past, to live a bitter life centered on an idea, which was sold for a price made by narrow-minded people. Far away from everything, he found peace in a house on the Mediterranean coast of the Spanish island of Mallorca, which he built for his family.

He received the Pritz’s award, the most prestigious award in the world of architecture, in 2003. His reaction was once again one of the characteristics of the spirit of an uncompromising visionary. That year, he gave an interview for the Sydney Herald Tribune where he said ‘If you like work of an architect, don’t give him gold medals, let him build cities’.

He lived his life knowing that his design brought about new movement of discourse in architecture and that he gave Australia time resistant national hallmark. He knew he didn’t need to go back to Sydney to see his master-piece – he just needed to close his eyes and it would be in front of him – flawless, intact by corrections and exempt from money talks.

One Friday night in 2004, he peacefully fell asleep next to his wife in their family home in his hometown. Next morning, he did not wake up. He died before sunrise due to a heart attack. I wonder, what images saw off the Danish genius to the other side.

Writes Marija Rašović

(Marija Rašović, originally from Podgorica, has a degree in journalism obtained at the Faculty of Political Sciences in Belgrade. She completed Masters in Madrid, and now lives and works in Abu Dhabi. And she travels… Her observations poured into words, esteem readers, you will be able to read here, on MNE magazin portal. )